|

Unit

3: The Case for Protection

Part

3: The Theory of Protectionism: Tariffs and Quotas

Protection essentially takes one of three forms: tariffs,

quotas, and non-tariff barriers. Tariffs are taxes levied

on a commodity crossing an international border. Quotas

are restrictions on the number of a certain good that can

be imported. Non-tariff barriers include all kinds of subsidies

and regulatory protection that doesn’t count as either

a tariff or a quota.

The basic motive for using tariffs is twofold: to protect

domestic industry from import competition and to generate

revenues for the government. For developing nations—such

as China—tariffs afford developing “infant”

industries the protection they need to mature. Moreover,

tariffs are an important source of revenue for such countries—as

they were for the United States until the early part of

the 20th century—since, even if developing countries

have income taxes in place (and can collect them), incomes

are frequently not high enough to sustain government operations

necessary for increasing economic growth. While tariffs

are more likely to be about revenue and fostering newly

developed industries in the developing world, for developed

nations the argument for their use rests squarely on jobs.

The effects within a given industry of a tariff include

higher prices, more domestic production, fewer imports,

tax revenue, and market inefficiencies because of the increase

in higher cost domestic production and loss of consumer

purchases caused by the higher market price. For example,

consider the following economic market analysis:

VIDEO: The Revenue and Protective Effects

of Tariffs

|

| When tariffs are levied against foreign

imports, domestic production and prices rise, imports

decline, and the government increases tax revenue. |

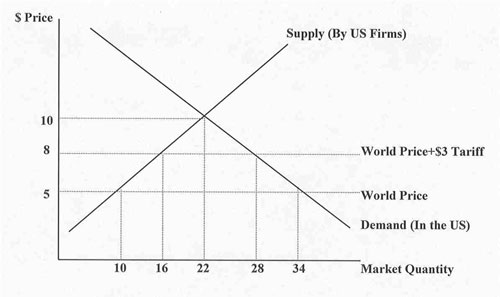

In the absence of any trade with the rest of the world,

this market would be in equilibrium where the supply of

the product produced by US firms equals the demand for the

product by US consumers – at a price of 10 and a quantity

of 22. According to economic theory, this would be an efficient

outcome because at $10 there are 22 buyers paying less than

they are willing to pay (based on their demand curve) and

22 sellers being paid more than they are willing to accept

(based on their supply curve). In other words, each of these

22 market transactions is transferring a product from someone

who places a lower value on the product (the seller) to

someone who places a higher value on the product (the buyer).

And this is the fundamental argument in favor of market

systems.

Now, let’s consider what would happen in this market

if the rest of the world, which could profitably sell this

product for $5, were permitted into the US. Facing competition,

domestic producers would be forced to lower their price

to $5, making them only willing to sell 10 units and causing

job losses. On the other hand, at a price of $5, there are

34 buyers who would willingly pay at least that, so they

buy the 10 units domestic producers are willing to make

and import the remaining 24. Theoretically, this outcome

is more efficient than a market without trade for two reasons:

First, at a lower price, there are more market transactions—which

are beneficial to consumers—and second, the higher

cost domestic production, which would have only been produced

and sold at prices above $5 (units 10–22) are now

replaced by lower cost—more efficiently produced—imports.

Indeed, free trade by almost any empirical account, is more

efficient than no trade, and on average benefits consumers

more that it harms producers. But the distribution of trade

effects are very skewed: millions of consumers pay lower

prices—and this adds up to a lot—but some workers

lose their jobs. So while it is reasonable to favor trade

on the grounds that the gains are bigger than the costs,

neither can one ignore the devastating impact it has on

an unfortunate few.

Now let’s suppose that lobbying efforts by the workers

and the domestic industry that is hurt from free trade are

successful, and the government imposes a $3 per unit tariff

on the import competition. In order to recover the cost

of the paying the tariff, the rest of the world is forced

to raise their price to $8 ($5 free trade price + $3 tariff

= $8). This higher price has two main effects:

-

domestic

firms benefit because at a price of $8 they will be able

to profitably increase production to 16 units (which will

require the employment of more workers)

-

domestic

consumers lose because the price they pay goes up by $3

and the number of market transactions falls from 34 to

28 (which means that 6 consumers who would have benefited

from buying the product at the free trade price are now

left out)

Additionally, the government

collects $36 in revenue from the tariff since each consumer

is paying $3 more for each of the 12 units imported (28

demanded – 16 domestically supplied = 12 units imported).

In the end analysis, whether protectionism is good or bad

for you is really a matter of where you stand, realizing,

of course, that on average the total costs to consumers

almost always outweighs the total benefits to the workers

and industry being protected.

VIDEO: Supply

and Demand Analysis of Protectionism

And finally, outside of the industry receiving protectionism,

tariffs have other, secondary effects which must also be

considered. For example, fewer imports means fewer dollars

in the hands of foreigners that can be used to buy home

country exports. Tariffs on imports (such as steel or parts

assemblies for cars, etc.) increase domestic production

costs. In general, they also raise the cost of living, and

they have a dampening effect on foreign GDP—which

will tamp down their demand for goods of all kinds, including

exports from the home country. For example, it is estimated

that the steel tariffs mentioned above cost far more Americans

their jobs in industries which relied on steel as an import

than steel workers jobs were saved.

VIDEO: Non-industry Effects of Protectionism

clip 1

VIDEO: Non-industry Effects of Protectionism

clip 2

It’s important to keep in mind the general context

in which the debate about tariffs takes place. The claim

that imports cost jobs looks self-evidently true on the

face of it, and so looks like a good case for tariffs. However,

empirical evidence clearly suggests that relatively few

jobs in the US economy as a whole are lost due to import

competition. In a recent speech, Ben Bernanke, a member

of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, quoted

an estimate that suggested that about 2% of total American

job loss per year was due to trade. Moreover, tariffs often

temporarily put off a day of reckoning that an inefficient

industry ought to have faced long ago. Concern for displaced

workers, in other words, need not lead to advocacy of tariffs.

WEBLINK: Ben

Bernanke

Quotas

As mentioned above, quotas are limits on the quantity of

a good that can be imported into a given country. In a static

sense, quotas and tariffs have similar effects, except that

tariffs provide tax revenue while quotas put more money

per unit in the pocket of the foreign manufacturer. Both

raise price, lower imports, help domestic producers at the

expense of consumers, and cause market inefficiencies. Dynamically,

however, quotas can be even more protectionist than tariffs—explaining

why domestic industry favors them and the WTO rejects them.

For example, if domestic demand goes up when a quota is

in place, then the production gap has to be made up by domestic

producers, which means even higher prices for consumers

(and more profits for domestic producers). On the other

hand, if a tariff is in place, then extra production can

be provided through additional imports, which usually means

that price goes up less quickly than with a quota in place.

VIDEO: Quotas

Versus Tariffs

|

All files © Copyright 2010 UNCG DCL

Please report any problems or errors to the Site

Admin

Our Privacy Policy

|

|

|