Part 3: Other Speech Limitations?

So far we have examined the "classic" limitations of free speech. These classic limits are:

- Harmful speech: Libelous or slanderous communication.

- Inciteful speech: Communication such as yelling fire in a crowded theater. This category includes the "fuzzy" concept of fighting words.

- Obscenity: Communication with no social, political, cultural, or artistic value-another "fuzzy" concept.

However, in addition to these classic limitations we should consider three other limitations that have been proposed in recent times. These "new" limitations consist of:

- Offensive speech: Includes flag burning, cursing, and even some art.

- Dangerous speech: Books on "how to build a bomb" or "how to make chemical weapons."

- Hate speech: Includes racial and ethnic epitaphs intended to harass or upset particular groups.

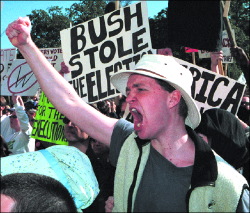

VIDEO: The following video brings to light several of the issues posed by both the classic and the new proposed limitations on speech.

Should we restrict offensive speech or dangerous speech?

When considering "offensive speech," we know that Mill would oppose any restriction based on offense. Certainly we would not want to say all offensive speech should be restricted (as what can we say that doesn't offend at least one person?). However, we might apply Feinberg's offense principle which would generate a limited restriction on offensive speech. According to Feinberg's offense principles, some forms of speech are so offensive that they justify a restriction. In addition, when such offensive speech is intended to offend, it may be motivated by a vice such as anger, spite, or hatred.

When considering "offensive speech," we know that Mill would oppose any restriction based on offense. Certainly we would not want to say all offensive speech should be restricted (as what can we say that doesn't offend at least one person?). However, we might apply Feinberg's offense principle which would generate a limited restriction on offensive speech. According to Feinberg's offense principles, some forms of speech are so offensive that they justify a restriction. In addition, when such offensive speech is intended to offend, it may be motivated by a vice such as anger, spite, or hatred.

For instance, take the case of flag burning. Imagine if during a Veteran's Day parade someone who hates the military decides to burn a flag as the veterans commemorate their sacrifice and the loss of their friends. The flag burner does this with the full knowledge and intent to deeply offend the veterans. What should we say about a case like this? Mill would understand that this action would give deep offense, but since offense does not qualify as a harm, the action is therefore permissible. The Supreme Court has ruled that flag burning is a form of free speech. (It cannot be fighting words since the ordinary American does not react violently, although veterans in this parade might well react violently.) Feinberg, however, would argue that this action can be prevented due to its offensive nature. Feinberg lays out some guidelines to determine if an offense was warranted. Among these guidelines Feinberg asked us to balance the following:

For instance, take the case of flag burning. Imagine if during a Veteran's Day parade someone who hates the military decides to burn a flag as the veterans commemorate their sacrifice and the loss of their friends. The flag burner does this with the full knowledge and intent to deeply offend the veterans. What should we say about a case like this? Mill would understand that this action would give deep offense, but since offense does not qualify as a harm, the action is therefore permissible. The Supreme Court has ruled that flag burning is a form of free speech. (It cannot be fighting words since the ordinary American does not react violently, although veterans in this parade might well react violently.) Feinberg, however, would argue that this action can be prevented due to its offensive nature. Feinberg lays out some guidelines to determine if an offense was warranted. Among these guidelines Feinberg asked us to balance the following:

The reasonable avoidability of the offense

- Assesses the intensity and duration of the offense as well as the anticipation of particular reaction. (Do you know in advance that your action will cause offense of high intensity and long duration?) In this case, the flag burner is well aware of the intense offense the act will have.

- The ability of unwilling witnesses to avoid the display. (Did they sit and watch a full hour of an offensive TV show only to later claim offense or were they stuck in a room with the action without a way to avoid or withdraw from it?) Clearly, those in the parade cannot easily avoid the flag burner as they march by, nor did they "seek out" the flag burner; he came to them.

- Did the witnesses "assume the risk" of being offended? (Did you pay to enter a freak-show, for example?) Given the attendance of a Veterans Day parade, one clearly does not expect to see a display of flag burning.

The reasonableness of the offender's actions

- The personal importance and social value of the action. Granted the flag burner may really have a message to share.

- The availability of alternative times and places to perform the action. The flag burner did not have to share his message at this particular time and place.

- The motive of the action. (Was this intended to offend?) It seems clear that the flag burner did intend to offend the veterans.

As a result, Feinberg would hold that in this case flag burning was not free speech and therefore should be restricted. This is not to say that Feinberg is against flag burning in all cases. Suppose the parade was instead a protest against government policies and some of the protesters burn flags. In re-examining the criteria above Feinberg would likely allow the flag burning in that case. In this sense, Feinberg offers a middle of the road approach between the total allowance of offensive acts like Mill advocates, and the complete restriction of offensive acts proposed by others. What might Aristotle have concluded conclude about offensive acts like flag burning? Though we cannot be certain, it would seem that in the Veterans Day parade case, Aristotle would find this action to be a less than virtuous display (especially for children and others to see at a parade). It seems likely that he would oppose flag burning in this case and some other cases as well on the grounds that it is disruptive to the state and sets a bad example for others.

As a result, Feinberg would hold that in this case flag burning was not free speech and therefore should be restricted. This is not to say that Feinberg is against flag burning in all cases. Suppose the parade was instead a protest against government policies and some of the protesters burn flags. In re-examining the criteria above Feinberg would likely allow the flag burning in that case. In this sense, Feinberg offers a middle of the road approach between the total allowance of offensive acts like Mill advocates, and the complete restriction of offensive acts proposed by others. What might Aristotle have concluded conclude about offensive acts like flag burning? Though we cannot be certain, it would seem that in the Veterans Day parade case, Aristotle would find this action to be a less than virtuous display (especially for children and others to see at a parade). It seems likely that he would oppose flag burning in this case and some other cases as well on the grounds that it is disruptive to the state and sets a bad example for others.

Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation ET AL.

This case focused on the offensive speech contained in a radio broadcast of George Carlin's in which he discussed the words you cannot say on TV. One listener complained about the language used in Carlin's broadcast, and the FCC took the broadcaster to court. The case went to the Supreme Court which, in another 5-4 ruling, found that the FCC could establish regulations concerning the broadcasting of such words. Below is a partial clip of Carlin's offending comedy bit. (If foul language bothers, you feel free to skip it.)

AUDIO: George Carlin-Seven Words You Can't Say On TV

Thought Question: Dangerous Speech

Specific to dangerous speech : What is the harm in my having a book on how to build a bomb? There is no harm or even threat of harm in simply having the information. Acting on it is another story. Yet, we can clearly see the advantage for security by restricting dangerous speech. Suppose I am a survivalist who is planning for the end of the world. I have built a large bunker in my backyard and have it stocked with books on how to build weapons to defend myself. Are there any grounds for restricting my access to this information? Is such a restriction practical? For instance, one famous case involves the book Hitman , a manual for how to commit murder, which was used in a multiple murder. Its author is really a housewife who wrote the book after watching detective shows and reading murder mysteries. (The publisher was sued and the book is no longer published, but the information is still out there.)