Part 1: John Stuart Mill

Mill argued that speech must be free even if offensive. The only legitimate restriction on speech is if it causes harm to others, or would most likely result in harm. This is reflected in many (but not all) of the legal limitations on speech in the U.S. Part of our focus will be to evaluate if the current legal limitations are enough, or should other forms of speech, most notably hate speech, be criminalized?

But first let us ask a more general question to establish the case for having any free speech. Why is free speech important?

Mill set out four reasons in support of free speech:

- "...if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility."

- "...though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied."

- "...even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds.

- "...the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction from reason or personal experience..."

One of the things Mill does not do is provide for any grounds under which offensive conduct can be restricted. Mill seems to think liberty allows us to speak or act offensively. But does liberty entail that all offensive conduct is morally acceptable? We will look at one philosopher who generally agrees with Mill, but offers an account of why we should limit liberty in some cases of offensive conduct.

So why is free speech important to Mill?

- It encourages new or better ideas to come out.

- It is conducive to the happiness of citizens if they can express themselves.

- Free and open expression allows us to use our capacities and think for ourselves.

Granted, most all of us would agree that free speech is important, but what are the limits of free speech? Before we go any further I'd like to test your own intuitions about free speech using the following cases:

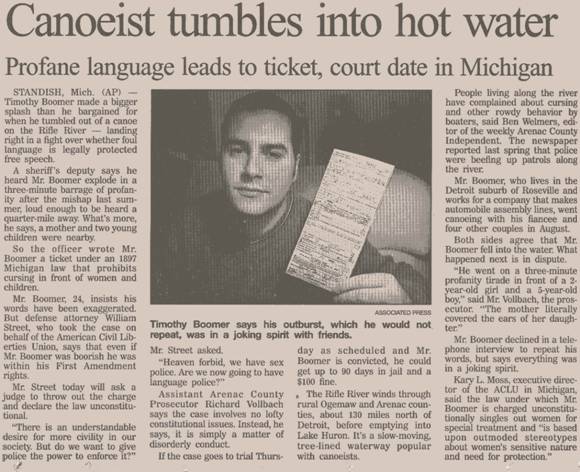

Case #1: The Canoeist

Mr. Boomer was eventually found guilty and paid a fine. Did he exceed the bounds of free speech? What was the harm in his actions? Notice the judge's reasoning for allowing the trial to go forward. He cites " fighting words " as the reason why Mr. Boomer's action was not free speech. According to the courts, fighting words are a subclass of harmful speech. Was the speech in this case likely to cause a fight? Keep this in mind as we will return to this concept later and ask if it qualifies as a harm.

Case #2: The Driver

Imagine a man driving on the freeway who is cut off by another driver. Is he free to curse at the other driver? How about honking his horn and shaking his fist (or perhaps offering a one finger salute)? Clearly these would both be offensive to the other driver but they do not strike us as harmful. Perhaps, like the canoeist it may be a case of "fighting words" (but this happens every day and rarely leads to a fight). Suppose instead of reacting as described above, our driver simply pulls out a realistic looking (but not really real) gun and taps it on the window as he passes drivers who offend him. Certainly there is no real harm, but might we not conclude that the mere threat of serious harm qualifies as a harm?

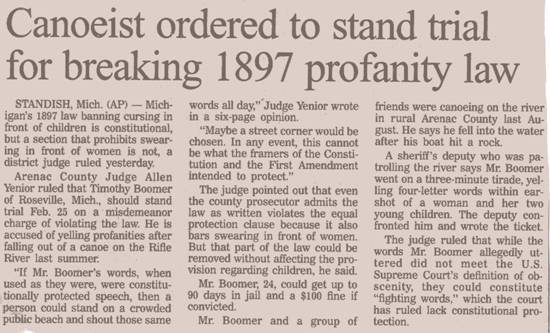

Case #3: Mooning

Case #3: Mooning

Clearly the act described to the right was both offensive and disrespectful . It is also quite clear that it was a form of expression that serves to communicate an opinion. Ask yourself this general question: Is mooning a form of free speech? Then consider why you answer as you do. Is there a harm in mooning? Is there a threat contained within mooning (as threats of harm are often counted as crossing the boundaries of free speech). If there is no harm or threat, what is it about mooning that would make it fall outside the bounds of free expression? (Nudity, of course, but on what grounds do you criminalize this?).

We can now establish two general criteria for the limitations on free speech.

- In order to be free speech it must not cause harm (What constitutes a harm again becomes the key question.).

- In order to be free speech it must not threaten harm or foreseeably lead to harm.

Setting aside the debate about what a harm is for a moment, what does the law say about the limits of free speech?