Part 2: Arguments against the Death Penalty

Now that we have reviewed the basic facts concerning the death penalty, let us examine the moral arguments concerning the death penalty. We have already mentioned the two arguments in favor of the death penalty (retribution and deterrence). However, as with other issues we have discussed, the burden of argument rests with the side claiming that something is immoral. To this end, let us examine six arguments against the death penalty. Keep in mind that none of these arguments is itself intended to be persuasive. Instead, we should examine all six as a “package deal” that may persuade us that the death penalty is immoral.

Argument #1

It is wrong to kill (we ALL have a right to life; no one deserves to be killed). Certainly this argument is often made. If murder is wrong, then two wrongs won't make a right, is one way commonly used to express this sentiment. (Or, that the death penalty demonstrates a lack of respect for human life.) This is also the basic argument of, among others, the previous Pope, who often sent letters to governors asking them to commute death sentences to life without parole. (We can only imagine a drawer in George W. Bush's house full of these letters.)

It is wrong to kill (we ALL have a right to life; no one deserves to be killed). Certainly this argument is often made. If murder is wrong, then two wrongs won't make a right, is one way commonly used to express this sentiment. (Or, that the death penalty demonstrates a lack of respect for human life.) This is also the basic argument of, among others, the previous Pope, who often sent letters to governors asking them to commute death sentences to life without parole. (We can only imagine a drawer in George W. Bush's house full of these letters.)

Argument #2

Innocent people will be murdered if we have the death penalty. Of course, we know that mistakes are made in the application of any justice system, but there is no way to undo the execution of an innocent person. If we had life without parole, there is still a chance to undo a wrongful conviction; the death penalty cannot be undone. Are innocent people executed? Estimates vary; some studies have claimed that dozens of innocent people have been executed in this century. Perhaps the best answer to this question is the fact that as of June 12 th 2000 , 87 inmates have been freed from death row since the 1977 Supreme Court decision re-authorized the use of the death penalty. Certainly, it is very likely that innocents have been executed (and will be) but how many is uncertain. Would you allow one innocent to be executed in order to execute 100 Tim McVeighs? If so, are you advocating a system that violates the right to life of some innocent people?

Innocent people will be murdered if we have the death penalty. Of course, we know that mistakes are made in the application of any justice system, but there is no way to undo the execution of an innocent person. If we had life without parole, there is still a chance to undo a wrongful conviction; the death penalty cannot be undone. Are innocent people executed? Estimates vary; some studies have claimed that dozens of innocent people have been executed in this century. Perhaps the best answer to this question is the fact that as of June 12 th 2000 , 87 inmates have been freed from death row since the 1977 Supreme Court decision re-authorized the use of the death penalty. Certainly, it is very likely that innocents have been executed (and will be) but how many is uncertain. Would you allow one innocent to be executed in order to execute 100 Tim McVeighs? If so, are you advocating a system that violates the right to life of some innocent people?

James McCloskey: Convicting the Innocent

McCloskey's central claim is that conviction of the innocent is far more common than anyone likes to admit. Those in the system hold that it is a rare occurrence, yet McCloskey holds it is more likely 10% of seriously violent offenses compared to “less than 1%” purported by those in the system. Once a conviction has  occurred, most people do not realize that the truth about guilt or innocence is irrelevant in the appeals process. Appeals are strictly to address legal mistakes during the lower level. Even if a jury believed false testimony or made an invalid inference of guilt, these are not grounds for appeal. In other words, our system is set up such that once a conviction is obtained, the question of guilt or innocence is largely ignored. One exception is if new evidence is produced, but this is rare as it would require funds and efforts to obtain such evidence on behalf of the convicted. Even in cases where post conviction DNA tests show unknown DNA at the crime scene, on the murder weapon, and where the convicted person's DNA is not found anywhere, appeals courts have ruled that this not proof of innocence; it just indicates an accomplice.

occurred, most people do not realize that the truth about guilt or innocence is irrelevant in the appeals process. Appeals are strictly to address legal mistakes during the lower level. Even if a jury believed false testimony or made an invalid inference of guilt, these are not grounds for appeal. In other words, our system is set up such that once a conviction is obtained, the question of guilt or innocence is largely ignored. One exception is if new evidence is produced, but this is rare as it would require funds and efforts to obtain such evidence on behalf of the convicted. Even in cases where post conviction DNA tests show unknown DNA at the crime scene, on the murder weapon, and where the convicted person's DNA is not found anywhere, appeals courts have ruled that this not proof of innocence; it just indicates an accomplice.

Beyond this, there are several systemic factors that cause the conviction of the innocent:

- Presumption of Guilt

Certainly we are taught “innocent until proven guilty” but reality does not bear this out. Think of major criminal trials you hear about before they go to trial. It is a stretch to assume that all the accusations and media attention does not lead to a presumption of guilt. Do any of you presume John Lee Malvo (the D.C. sniper suspect) to be innocent after hearing in the media of his confession and other evidence? Most people believe that someone must have done something to cause these charges and all the media focus upon them. This not only applies to jurors but also to lawyers, judges, police, and investigators. Once someone becomes the focus of investigation and media attention, the presumption of guilt becomes natural such that even investigators may ignore other suspects or leads as they don't fit the “direction of the investigation.” This was demonstrated in the case of Richard Jewel, who became the sole suspect in the Atlanta Olympic bombing investigation such that some in the media declared that he did it. It turns out after weeks of media accusations and searches of his home that he was found to be an innocent bystander. Given the focus on Richard Jewel, how many other leads were not pursued in time to catch the real bomber? Even defense attorneys in cases have admitted they never believed in their client's innocence. Are we to believe this did not impair many of them from perusing the best defense for their client?

suspect) to be innocent after hearing in the media of his confession and other evidence? Most people believe that someone must have done something to cause these charges and all the media focus upon them. This not only applies to jurors but also to lawyers, judges, police, and investigators. Once someone becomes the focus of investigation and media attention, the presumption of guilt becomes natural such that even investigators may ignore other suspects or leads as they don't fit the “direction of the investigation.” This was demonstrated in the case of Richard Jewel, who became the sole suspect in the Atlanta Olympic bombing investigation such that some in the media declared that he did it. It turns out after weeks of media accusations and searches of his home that he was found to be an innocent bystander. Given the focus on Richard Jewel, how many other leads were not pursued in time to catch the real bomber? Even defense attorneys in cases have admitted they never believed in their client's innocence. Are we to believe this did not impair many of them from perusing the best defense for their client? - Police Perjury?

“In almost any factual hearing or trial, someone is committing perjury; and if we investigate all of those things, literally we would be doing nothing but prosecuting perjury cases.” (Philadelphia District Attorney.) Everyone assumes that the guilty and their supporters will lie to protect themselves, but most forget to assume the same for the police, who also lie to protect themselves, each other, and to aid the prosecution. As one New Jersey officer put it, “They [the defense] lie, so we [police] lie. I don't know one of my fellow officers who hasn't lied under oath.” Or the New York judge who said, “Oh, sure, cops often lie on the stand.” Just as the guilty have an interest in lying, so too do the police; yet most juries will accept police testimony as fact and presume the defense to be lying. - False Prosecution Witnesses

Just as the police often have an interest in lying to protect themselves and promote the prosecution's case, so too do many prosecution witnesses. Often this is done with subtle prosecution guidance (“isn't this what you saw the defendant do?”). Think of many criminal cases where the prime prosecution witnesses are themselves criminals who, in exchange for testimony against the defendant, are offered immunity or plea deals. Among other things, these cases include “jailhouse confessions” or are the result of police/prosecutors using “prisoner's dilemma” tactics which all but encourage lying. For instance, the use of a prisoner's dilemma can result in Betty, who pulled the trigger, testifying that Alf, who happened to be at the scene, did the deed (and that she was the innocent bystander to Alf's crime). If Betty's story is more likely to convict Alf than Alf's is to convict Betty, why wouldn't a prosecutor charge Alf with the crime? Another example is the drug trafficker who uses his girlfriend's car to transport drugs suddenly claims that he had no idea what was in the trunk and successfully testifies that she is the drug trafficker.

too do many prosecution witnesses. Often this is done with subtle prosecution guidance (“isn't this what you saw the defendant do?”). Think of many criminal cases where the prime prosecution witnesses are themselves criminals who, in exchange for testimony against the defendant, are offered immunity or plea deals. Among other things, these cases include “jailhouse confessions” or are the result of police/prosecutors using “prisoner's dilemma” tactics which all but encourage lying. For instance, the use of a prisoner's dilemma can result in Betty, who pulled the trigger, testifying that Alf, who happened to be at the scene, did the deed (and that she was the innocent bystander to Alf's crime). If Betty's story is more likely to convict Alf than Alf's is to convict Betty, why wouldn't a prosecutor charge Alf with the crime? Another example is the drug trafficker who uses his girlfriend's car to transport drugs suddenly claims that he had no idea what was in the trunk and successfully testifies that she is the drug trafficker. - Prosecutorial Misconduct

There is ample incentive and opportunity for prosecutors to elicit false testimony, distort the facts, or suppress evidence damaging to their case. These tactics severely diminish the defendant's ability to make a case for innocence. Many cases of misconduct are known. (The author cites several cases, including a 1981 case of Texas Rangers intimidating witnesses into fingering someone who they latter admitted they did not see commit the crime and a New Jersey case where a year after a crime, a “surprise eyewitness” appeared and testified against a man, only years later to admit he gave false testimony under pressure form the prosecutors.) Yet this is likely only the tip of the iceberg. For every case of prosecutorial misconduct we know about, there are likely dozens we don't (the same claim would apply to false testimony and police perjury as well). Prosecutorial misconduct has occurred everywhere from minor cases to death penalty cases. It does not always require a specific act by prosecutors but can occur by omitting certain evidence that would demonstrate or lead to the conclusion of innocence. The motives of prosecutors are often political in nature. What is important is in garnering a conviction for many crimes, rather than convicting the right person. This was the case in Florida a few years ago where a prosecutor charged two separate defendants for the same crime, using the defendant in one trial as a witness against the other in their trial. In doing so, the prosecutor overtly demonstrates that he is uninterested in who is guilty but seeks only to garner a conviction for the crime. - Shoddy Police Work

Police are often overburdened with investigations. The pressure to “clear” cases quickly with convictions provides an incentive to take the easy way out. This often entails focusing on the first suspect they can find and ignoring other possibilities (as they will take time, resources, and might lead to an unsolved case). One case that fits this model occurred in Florida a couple years ago where a tourist was shot “by a young black man.” Within an hour the police picked up a 15-year-old African American boy who was walking to work at a nearby fast food establishment. The boy was immediately taken before the elderly spouse of the victim (in handcuffs) where she was asked if this was the shooter. The spouse said, “yes,” and the boy was charged and found guilty, based upon the spouse's testimony and the police testimony that the boy “acted guilty.” No other investigation was performed or evidence presented as the community desired a quick and speedy conviction (to avoid tourism decline). Despite the boy's parents' testimony that he was home at the time of the murder, the jury believed the spouse and police, as the parents would likely lie to protect their son. The real shooter was caught months later (after the boy's attorney conducted his own investigation, finding the murder weapon in a dumpster and other witnesses to the murderer's escape from the scene). Only after overwhelming evidence to the contrary was the boy released. A thorough investigation would have demonstrated the boy's innocence in the first place. - Incompetent Defense Counsel

A great many defendants rely upon public defenders who are often incompetent. The Texas death penalty case where the defense attorney slept through hours of the trial is one example (the judge and prosecutor did not dispute this fact, but the Texas appeals courts found that the sleeping defense attorney was not grounds to overturn the conviction). Not only are good defense attorneys hard to find, but the number of defense attorneys is in decline. Of 30,000 attorneys in New Jersey , the number doing criminal defense work is in the hundreds. Further, 85% of New Jersey criminal defendants use public defenders. Public defenders have higher caseloads than other attorneys, lower budgets, and are paid far less. The result is less time to prepare a case, less incentive to provide a good defense, and less ability to investigate or obtain expert testimony. This puts defendants at a severe disadvantage before the trail even begins. Would O. J. be playing golf in Florida today had he used public defenders?

case where the defense attorney slept through hours of the trial is one example (the judge and prosecutor did not dispute this fact, but the Texas appeals courts found that the sleeping defense attorney was not grounds to overturn the conviction). Not only are good defense attorneys hard to find, but the number of defense attorneys is in decline. Of 30,000 attorneys in New Jersey , the number doing criminal defense work is in the hundreds. Further, 85% of New Jersey criminal defendants use public defenders. Public defenders have higher caseloads than other attorneys, lower budgets, and are paid far less. The result is less time to prepare a case, less incentive to provide a good defense, and less ability to investigate or obtain expert testimony. This puts defendants at a severe disadvantage before the trail even begins. Would O. J. be playing golf in Florida today had he used public defenders? - Nature of Convicting Evidence

Contrary to public belief, juries do not commonly convict based upon the evidence presented (as typically seen on TV). Instead, juries convict most commonly based upon which witnesses' testimony they believe. For instance, the Florida boy's case was decided when the jury choose to believe the victim's spouse and police over the defendant's parents. Eyewitness testimony, even from that of the victim, is common evidence used to gain conviction, yet this is some of the most unreliable evidence presented. Some examples mentioned in the article include:

- The rape victim who identified as her rapist a man who had a vasectomy well before the attack occurred (despite evidence of sperm left within her).

- The clerk who identified a 6'5” man as her robber (despite testifying that he was her height, she was 5'6”.)

- The kidnapped woman who spent 2 days with her attacker later identifying a man with an iron-clad alibi. Despite this, the jury convicted the man anyway in the belief that 2 days with someone would make correct identification a certainty.

The unreliability of eyewitness testimony is a well known phenomenon (one we need not delve into here). Suffice it to say that if witness testimony is the most commonly used to determine conviction, and

Given these factors, the conviction of the innocent likely occurs far more than we like to admit. The author contends that at least 10% of convictions are of innocent people. The question remains, what are we to do about this? The question for the utilitarian becomes, is a 10% innocent rate acceptable given the system nets a majority of the guilty? Do we sacrifice one innocent to get nine guilty, or do we allow, say, three guilty people to get off to protect one innocent person? is the most unreliable evidence, then it stands to reason that a great many innocent people are convicted. Further, even where scientific evidence is offered, there is reason to be skeptical. Several cases have emerged where scientific evidence offered by crime labs and expert witnesses has been found to be in error or even falsified to obtain a conviction. In other cases lab experts have exaggerated evidence in order to please the prosecution or, where experts disagree, only those with the view favorable to the prosecution are put on the stand. As crime labs are funded by the state, this further provides advantages to prosecutors that defense attorneys cannot match. Defense attorneys not trained in scientific evidence or who lack the funds to hire their own experts further exacerbate the prosecution's advantage.

is the most unreliable evidence, then it stands to reason that a great many innocent people are convicted. Further, even where scientific evidence is offered, there is reason to be skeptical. Several cases have emerged where scientific evidence offered by crime labs and expert witnesses has been found to be in error or even falsified to obtain a conviction. In other cases lab experts have exaggerated evidence in order to please the prosecution or, where experts disagree, only those with the view favorable to the prosecution are put on the stand. As crime labs are funded by the state, this further provides advantages to prosecutors that defense attorneys cannot match. Defense attorneys not trained in scientific evidence or who lack the funds to hire their own experts further exacerbate the prosecution's advantage. - The rape victim who identified as her rapist a man who had a vasectomy well before the attack occurred (despite evidence of sperm left within her).

Argument #3

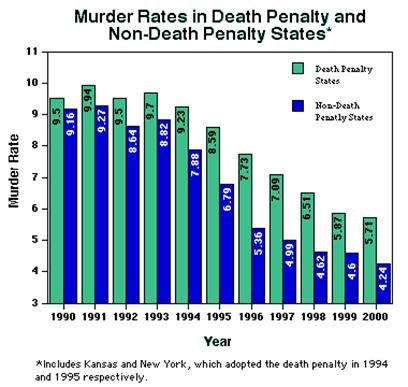

The death penalty is not a deterrent. This is a strong argument against the death penalty because, if it is correct, then it eliminates one of the two prime reasons for the death penalty (the prime reason why utilitarians, like Mill, support it). Is the death penalty a deterrent? It is commonly thought that it is, yet even the Supreme Court concluded that the evidence for deterrence was inconclusive (and many studies have tried to show that it is a deterrent). Clearly, deterrence does work in some instances. When a thief contemplates his hand being chopped![]() off for stealing a candy bar in Saudi Arabia , is he not deterred? (Statistics show he is.) Perhaps there is an explanation about why the death penalty does not deter. With rare exception, death penalty cases are cases of murder. Murder, unlike many other crimes, is often a crime of impulse or irrationality, and this may be why the death penalty does not deter people. However, we might appeal to our own intuitions to see why the death penalty might not be a deterrent. If given a choice between being executed by lethal injection or being put in maximum security prison for the rest of your life without parole, which would you choose? If the death penalty is a deterrent, we should see people overwhelmingly choose life without parole. We would also expect to see more Ohioans commit their murders in Michigan to avoid the death penalty ( Michigan does not execute and Ohio does). Yet, we do not see a higher murder rate in states without the death penalty than in states with it (see graphic below). Even if the death penalty is not a deterrent, this does not mean that it couldn't be made to be a deterrent. Can you imagine ways we might make the death penalty more of a deterrent? Would increasing its deterrent effect make it more likely that people's rights would be violated?

off for stealing a candy bar in Saudi Arabia , is he not deterred? (Statistics show he is.) Perhaps there is an explanation about why the death penalty does not deter. With rare exception, death penalty cases are cases of murder. Murder, unlike many other crimes, is often a crime of impulse or irrationality, and this may be why the death penalty does not deter people. However, we might appeal to our own intuitions to see why the death penalty might not be a deterrent. If given a choice between being executed by lethal injection or being put in maximum security prison for the rest of your life without parole, which would you choose? If the death penalty is a deterrent, we should see people overwhelmingly choose life without parole. We would also expect to see more Ohioans commit their murders in Michigan to avoid the death penalty ( Michigan does not execute and Ohio does). Yet, we do not see a higher murder rate in states without the death penalty than in states with it (see graphic below). Even if the death penalty is not a deterrent, this does not mean that it couldn't be made to be a deterrent. Can you imagine ways we might make the death penalty more of a deterrent? Would increasing its deterrent effect make it more likely that people's rights would be violated?

(Source: http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/ 2005)

Argument #4

The death penalty is more expensive than life without parole. It is commonly thought that we  spend more on life without parole than we do on death penalty cases. This is simply not the case. Remember, the average time before execution is nine years. This means we are paying for:

spend more on life without parole than we do on death penalty cases. This is simply not the case. Remember, the average time before execution is nine years. This means we are paying for:

- Nine years on death row (which is much more expensive since we ensure suicide does not occur and provide extra security).

- Nine years of court costs, prosecution costs, and in most cases defense costs as well (not to mention transportation to court under maximum security).

Though estimates vary by state, when all is said and done, we pay around 2–3 million per execution. To equal this amount we would have to pay $50,000 per year of imprisonment for 50 years in order to spend the same amount as an execution. Most states spend far less per year, and few people live for 50 years in prison.

POLL QUESTION: Do you believe the death penalty deters others from committing murder?

Argument #5

The death penalty discriminates against the poor and minorities. This is based on numerous facts and studies that show that whites and wealthy persons who are charged with the same crimes are far less likely to receive the death penalty than the poor or minorities. These studies also indicate that who is murdered also plays a role. For instance, a poor black man who kills a wealthy white man is far more likely to receive the death penalty than a white man who kills a black man. I'm sure we are already aware that wealthy clients are more likely to get lighter sentences if for no other reason than they hire far better lawyers. (If O.J. Simpson were poor and using a public defender, do you think he would have been found not guilty?)

Consider the following evidence in support of this argument:

Gender and Race of Defendants Executed and Their Victims *

(As of April 1, 2002 )

* Source: NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc, Spring 2002

The issue of discriminatory application is not new. The Supreme Court famously looked at it in the 1987 case McCleskey v. Kemp.

WEBLINK READING : Click here to read McCleskey v. Kemp.

Ultimately the court ruled against the claim that the death penalty was racially discriminatory. Still, the issue has remained as more evidence demonstrates that minorities and the poor end up on death row more often than other groups who commit the same crimes.

POLL QUESTION: Did the court reach the right conclusion in McCleskey?

Argument #6

The death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment. This argument has been the focus of most of the legal challenges to the death penalty. It tends to focus on how the death penalty is applied and what sorts of punishment is used. Remember that concern over cruel and unusual punishment is behind the evolution of the methods used in executions. Historically, hanging replaced the more “medieval” methods, electrocution, replaced hanging, the gas chamber was introduced as more humane than electrocution and finally lethal injection has been claimed the most humane. Electrocution itself has been the target of this claim as there have been several “botched” electrocutions. In some cases people have had to be electrocuted a second time; in others, flames have shot out from the head and bleeding from under the hood. To get a further sense of what electrocution can do, students are free to (but not required) to view the following video and photos. The video is a Hollywood dramatization of a botched execution (from the “Green Mile”); the photos are post execution shots of a Florida execution from 1999. WARNING: they are graphic.

VIDEO CLIP: From The Green Mile.

WEBLINK: “Electric Chair.”

The argument that the death penalty is cruel and usual has also been made that a 10-year or more delay in execution is also cruel and unusual, though no court has accepted this argument to date. Where this argument has been successful is in two recent cases. In 2002 the Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that it was unconstitutional to execute the mentally retarded. In 2005 the Supreme Court ruled in Roper v. Simmons that it was unconstitutional to execute anyone from a crime committed under the age of 18. Prior to these decisions, a great many death row inmates were mentally retarded and about 1% were juveniles. The last juvenile executed in the United States occurred in Georgia in 1993. Both decisions were fairly controversial. Here is a summary of the Roper v. Simmons decision which was 5-4.

WEBLINK READING : Click here to read Roper v. Simmons.

POLL QUESTION: Did the court decide correctly in Roper v. Simmons?

One need not accept all six of these arguments in order to see that it is a powerful case against the death penalty. When you balance these six arguments against the argument of retribution (since the death penalty has not been proven as a deterrent), can you still offer a defense of the death penalty?