Part 4: Paternalism, Moral Feeling or Moral Reason

WEBLINK: Click here to read Gerald Dworkin's article on paternalism.

Mill's harm principle, Dworkin argues, is really two claims. The first is that harm to others is sometimes a reason to criminalize behavior. The second is that an individual's own good is never a reason to criminalize behavior. Dworkin accepts the first claim but questions the second, which is a rejection of paternalism.

Mill's harm principle, Dworkin argues, is really two claims. The first is that harm to others is sometimes a reason to criminalize behavior. The second is that an individual's own good is never a reason to criminalize behavior. Dworkin accepts the first claim but questions the second, which is a rejection of paternalism.

Paternalism is the idea that we are justified in interfering in your liberty strictly for your own good. This interference may be by preventing you from undertaking a harmful or risky action (using drugs) or it may be compelling you by law to act in order to protect yourself (wearing a seat belt). Dworkin lists several paternalistic laws:

- Requiring motorcycle helmets.

- No swimming without lifeguards on duty.

- Laws against suicide.

- Restricting women and children from certain jobs.

- Laws against homosexuality and other sexual conduct between consenting adults.

- Drug laws-especially requiring a prescription for drugs which do not cause anti-social behavior.

- Laws requiring a license to engage in the practice. (What does he mean? He doesn't mean doctors.)

- Laws requiring retirement purchases. (Social Security)

- Laws against gambling.

- Regulation of interest rates.

- Laws against dueling

In addition:

- Laws regulating contracts (no selling yourself into slavery).

- Laws restricting the assumption of risk as a defense when safety is ignored.

- Not allowing consent of the victim as a defense for murder.

- Civil commitment of the unwilling on grounds they might hurt themselves.

Interestingly enough Dworkin adds some further forms of paternalism, which at the time were not laws-and believe me-we never thought they would become laws.

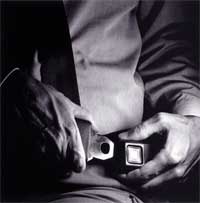

- Safety belts in automobiles (Dworkin in 1971 thought that this could be required by not allowing you to sue for damages if you didn't wear your seat belt. . . Behold Dworkin, the power of the fines!)

- Ban sale of cigarettes (Hasn't happened yet, but we are well on our way such that the possibility isn't laughable like it used to be.)

From this list Dworkin makes a distinction between pure and impure cases of paternalism.

Pure Paternalism is where the class of persons whose liberty is restricted is identical to class of persons intended to benefit from that restriction. Examples: laws requiring seatbelts or laws against suicide.

Impure Paternalism is where the class of persons whose liberty is restricted is not identical to class of persons intended to benefit from that restriction. Examples: banning the manufacture of cigarettes (or other goods) on the grounds that people may harm themselves by using them. Notice, this would not be the same as the requirement that you warn people of the danger of products. Instead, this would say even though everyone knows your product may be harmful, we are preventing you from selling it on the grounds that the buyer may misuse it and harm themselves. What other products might fit this model?

Thought Question: On Paternalism

Does one type of paternalism seem more plausible or are both equal?

Dworkin finds Mill's objection to paternalism to be out of step with his other writings. Mill categorically eliminates paternalism, holding that only self-protection allows us to interfere with the liberty of others. Yet compare this to Mill's view on lying and justice:

Yet that even this rule [against Lying], sacred as it is, admits of possible exception. . . where withholding of some fact. . . would save an individual. . . from great and unmerited evil.

Like all other obligations of justice already spoken of, this one is not regarded as absolute, but as capable of being overruled by a stronger obligation of justice on the other side.

In both cases Mill, as most utilitarians are known to do, supports exceptions. Dworkin wonders why Mill does not apply this to allow for paternalism as well? Dworkin says here that even Mill should have allowed for some paternalism when individuals clearly do not know their own interest (Like Alf's decision not to wear his seat belt for fear of burning to death). Mill did allow for paternalism in the case of selling into slavery; why as a utilitarian should all other forms be prohibited? The best that Dworkin thinks Mill can argue for on utilitarian grounds is that the burden is placed on the paternalist to justify a restriction on liberty rather than on the person who wants to make use of their liberty without paternalistic interference. Notice, Dworkin says nothing about libertarian justification for the harm principle and its prohibition on paternalism.

So when is paternalism justified according to Dworkin?

So when is paternalism justified according to Dworkin?

Strong Case. In The Odyssey Odysseus commands his men to tie him to the mast and refuse all orders to be set free, because he knows the power of the Sirens to enchant men with their songs. Since we know what Odysseus wants, we are simply applying it against what he feared (that he would be enchanted).

Justified paternalism is rarely like this as we do not get people to consent in advance to specific paternalistic measures. Instead, we might obtain people's consent to a system of government which will use paternalism in limited ways to ensure our safety.

We might make a claim here about choice. If you were offered a choice between a libertarian state (without paternalism) or a similar state (with limited paternalism), which would you consent to?

A system of paternalism that he is speaking of is a sort of social insurance against irrational, uninformed, or accidental behavior. For instance, you might even agree that you should wear your seat belt but when left to your own devices you forget to put it on. However, with an occasional advertising campaign, "Seat Belt Enforcement Month: Click It or Ticket," and threat of an expensive fine, you suddenly find motive to wear your seat belt. Have you been deprived of your liberty or have we actually helped you do what you wanted to in the first place? Isn't preventing suicide like this? If we asked you most days, you would oppose ever killing yourself, but on one particular day you decide to try. Are we not protecting your liberty and upholding your desires by stopping you (at least temporarily) for a "cooling off period"? How many people years later conclude that you should have let them die?

Further, take smoking. Smokers might be:

- Unaware of the real risks.

- Be aware of the real risks, but lack the willpower to quit.

- Be aware of the risks but make an irrational calculation that they are not a big deal because they will take so long to occur.

In each of these situations, would not paternalism serve to correct irrational, ignorant, or undesired actions that lead to great harm? How would letting these people go on smoking enhance their liberty given the reasons for their actions?

In each of these situations, would not paternalism serve to correct irrational, ignorant, or undesired actions that lead to great harm? How would letting these people go on smoking enhance their liberty given the reasons for their actions?

Dworkin also wishes to limit paternalism by requiring it to balance the "reducing of high risk of serious injury" and the loss to the person restricted. For example, being compelled to wear a seat belt yields significant harm reduction with an insignificant cost to the person. Alternatively, banning mountain climbing may yield significant harm reduction (as many climbers die each year or have other injuries) but also poses a significant cost to the person by precluding their favored life's hobby or livelihood.

In the end, paternalism is justified on Dworkin's account but the burden of proof is high. As he says: "Better that two men ruin themselves than one man be unjustly deprived of liberty."